How Is Relief in Art Different Than a 3d Sculptre

The term relief refers to a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same fabric. The term relief is from the Latin verb relevo, to heighten. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the sculpted material has been raised to a higher place the groundwork plane.[1] When a relief is carved into a flat surface of stone (relief sculpture) or wood (relief etching), the field is actually lowered, leaving the unsculpted areas seeming higher. The arroyo necessitates a lot of chiselling away of the groundwork, which takes a long time. On the other mitt, a relief saves forming the rear of a discipline, and is less delicate and more than securely fixed than a sculpture in the round, particularly i of a standing figure where the ankles are a potential weak point, particularly in stone. In other materials such as metal, dirt, plaster stucco, ceramics or papier-mâché the form can be just added to or raised upward from the background, and monumental statuary reliefs are made by casting.

There are unlike degrees of relief depending on the degree of projection of the sculpted form from the field, for which the Italian and French terms are yet sometimes used in English. The total range includes high relief (alto-rilievo, haut-relief),[ii] where more than 50% of the depth is shown and there may be undercut areas, mid-relief (mezzo-rilievo), low relief (basso-rilievo), or French: bas-relief (French pronunciation: [baʁəljɛf]), and shallow-relief or rilievo schiacciato,[3] where the plane is only very slightly lower than the sculpted elements. There is likewise sunk relief, which was mainly restricted to Ancient Arab republic of egypt (see beneath). However, the distinction between loftier relief and depression relief is the clearest and most important, and these ii are more often than not the simply terms used to discuss near piece of work.

The definition of these terms is somewhat variable, and many works combine areas in more than 1 of them, rarely sliding between them in a single figure; appropriately some writers prefer to avoid all distinctions.[four] The opposite of relief sculpture is counter-relief, intaglio, or cavo-rilievo, [5] where the form is cut into the field or background rather than ascent from information technology; this is very rare in monumental sculpture. Hyphens may or may non be used in all these terms, though they are rarely seen in "sunk relief" and are usual in "bas-relief" and "counter-relief". Works in the technique are described as "in relief", and, specially in awe-inspiring sculpture, the piece of work itself is "a relief".

A confront of the high-relief Frieze of Parnassus round the base of the Albert Memorial in London. Most of the heads and many feet are completely undercut, but the torsos are "engaged" with the surface behind

Reliefs are common throughout the world on the walls of buildings and a variety of smaller settings, and a sequence of several panels or sections of relief may represent an extended narrative. Relief is more suitable for depicting complicated subjects with many figures and very active poses, such as battles, than gratis-continuing "sculpture in the round". Nearly ancient architectural reliefs were originally painted, which helped to define forms in low relief. The subject of reliefs is for convenient reference assumed in this article to be usually figures, but sculpture in relief oft depicts decorative geometrical or foliage patterns, equally in the arabesques of Islamic art, and may be of whatsoever field of study.

A mutual mixture of high and low relief, in the Roman Ara Pacis, placed to be seen from beneath. Low relief ornament at lesser

Rock reliefs are those carved into solid rock in the open air (if inside caves, whether natural or human-made, they are more likely to be called "rock-cut"). This blazon is found in many cultures, in particular those of the Ancient About Due east and Buddhist countries. A stele is a unmarried standing stone; many of these carry reliefs.

Types [edit]

The distinction between high and low relief is somewhat subjective, and the ii are very often combined in a single work. In particular, nearly subsequently "high reliefs" incorporate sections in low relief, usually in the background. From the Parthenon Frieze onwards, many unmarried figures in large awe-inspiring sculpture have heads in high relief, simply their lower legs are in low relief. The slightly projecting figures created in this way work well in reliefs that are seen from beneath, and reflect that the heads of figures are usually of more interest to both creative person and viewer than the legs or feet. As unfinished examples from various periods show, raised reliefs, whether high or low, were normally "blocked out" by marking the outline of the figure and reducing the background areas to the new groundwork level, work no doubt performed past apprentices (come across gallery).

Low relief or bas-relief [edit]

A depression relief is a projecting image with a shallow overall depth, for example used on coins, on which all images are in low relief. In the lowest reliefs the relative depth of the elements shown is completely distorted, and if seen from the side the epitome makes no sense, but from the front the small variations in depth annals as a iii-dimensional image. Other versions distort depth much less. The term comes from the Italian basso rilievo via the French bas-relief (French pronunciation: [baʁəljɛf]), both meaning "low relief". The former is at present a very former-fashioned term in English, and the latter is becoming so.

It is a technique which requires less work, and is therefore cheaper to produce, as less of the groundwork needs to be removed in a carving, or less modelling is required. In the fine art of Ancient Egypt, Assyrian palace reliefs, and other ancient Nigh Eastern and Asian cultures, a consistent very low relief was ordinarily used for the whole composition. These images would usually be painted subsequently carving, which helped ascertain the forms; today the pigment has worn off in the great majority of surviving examples, merely minute, invisible remains of paint tin can usually be discovered through chemic ways.

A low-relief dating to circa 2000 BC, from the kingdom of Simurrum, modern Republic of iraq

The Ishtar Gate of Babylon, now in Berlin, has low reliefs of big animals formed from moulded bricks, glazed in colour. Plaster, which made the technique far easier, was widely used in Arab republic of egypt and the Almost East from antiquity into Islamic times (latterly for architectural decoration, as at the Alhambra), Rome, and Europe from at to the lowest degree the Renaissance, as well every bit probably elsewhere. Yet, it needs very good conditions to survive long in unmaintained buildings – Roman decorative plasterwork is mainly known from Pompeii and other sites buried by ash from Mount Vesuvius. Low relief was relatively rare in Western medieval fine art, but may be establish, for example in wooden figures or scenes on the insides of the folding wings of multi-panel altarpieces.

The revival of low relief, which was seen as a classical fashion, begins early on in the Renaissance; the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini, a pioneering classicist building, designed by Leon Battista Alberti around 1450, uses low reliefs past Agostino di Duccio within and on the external walls. Since the Renaissance plaster has been very widely used for indoor ornamental work such as cornices and ceilings, just in the 16th century information technology was used for large figures (many too using high relief) at the Chateau of Fontainebleau, which were imitated more crudely elsewhere, for example in the Elizabethan Hardwick Hall.

Shallow-relief, in Italian rilievo stiacciato or rilievo schicciato ("squashed relief"), is a very shallow relief, which merges into engraving in places, and tin can be difficult to read in photographs. It is often used for the background areas of compositions with the principal elements in low-relief, but its use over a whole (usually rather small) piece was perfected past the Italian Renaissance sculptor Donatello.[6]

In later Western art, until a 20th-century revival, low relief was used mostly for smaller works or combined with higher relief to convey a sense of distance, or to give depth to the composition, especially for scenes with many figures and a landscape or architectural background, in the same style that lighter colours are used for the same purpose in painting. Thus figures in the foreground are sculpted in high-relief, those in the background in low-relief. Depression relief may use any medium or technique of sculpture, stone carving and metal casting existence most common. Large architectural compositions all in depression relief saw a revival in the 20th century, beingness popular on buildings in Art Deco and related styles, which borrowed from the ancient low reliefs now bachelor in museums.[7] Some sculptors, including Eric Gill, accept adopted the "squashed" depth of low relief in works that are actually free-standing.

-

"Blocked-out" unfinished depression relief of Ahkenaten and Nefertiti; unfinished Greek and Persian high-reliefs evidence the aforementioned method of beginning a piece of work.

-

-

Atropos cutting the thread of life. Aboriginal Greek low relief

-

Donatello, Madonna and Child in rilievo stiacciato or shallow relief

-

French 20th-century low relief

Mid-relief [edit]

Mid-relief, "half-relief" or mezzo-rilievo is somewhat imprecisely divers, and the term is not oft used in English language, the works usually existence described as depression relief instead. The typical traditional definition is that simply up to one-half of the subject projects, and no elements are undercut or fully disengaged from the groundwork field. The depth of the elements shown is usually somewhat distorted.

Mid-relief is probably the most mutual type of relief found in the Hindu and Buddhist art of India and Southeast Asia. The low to mid-reliefs of second-century BCE to 6th-century CE Ajanta Caves and 5th to 10th-century Ellora Caves in India are rock reliefs. Most of these reliefs are used to narrate sacred scriptures, such as the 1,460 panels of the 9th-century Borobudur temple in Primal Coffee, Republic of indonesia, narrating the Jataka tales or lives of the Buddha. Other examples are low reliefs narrating the Ramayana Hindu epic in Prambanan temple, too in Coffee, in Cambodia, the temples of Angkor, with scenes including the Samudra manthan or "Churning the Ocean of Milk" at the twelfth-century Angkor Wat, and reliefs of apsaras. At Bayon temple in Angkor Thom in that location are scenes of daily life in the Khmer Empire.

High relief [edit]

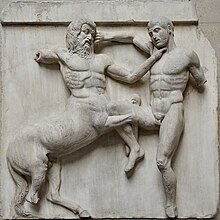

Loftier relief metope from the Classical Greek Parthenon Marbles. Some front limbs are actually discrete from the groundwork completely, while the centaur's left rear leg is in low relief.

High relief (or altorilievo, from Italian) is where in full general more than one-half the mass of the sculpted figure projects from the background. Indeed, the most prominent elements of the composition, especially heads and limbs, are ofttimes completely undercut, detaching them from the field. The parts of the subject that are seen are normally depicted at their full depth, unlike low relief where the elements seen are "squashed" flatter. High relief thus uses essentially the aforementioned style and techniques equally free-standing sculpture, and in the case of a single figure gives largely the same view equally a person standing straight in front end of a complimentary-standing statue would have. All cultures and periods in which large sculptures were created used this technique in monumental sculpture and architecture.

Most of the many grand figure reliefs in Ancient Greek sculpture used a very "high" version of high relief, with elements oftentimes fully gratis of the background, and parts of figures crossing over each other to indicate depth. The metopes of the Parthenon accept largely lost their fully rounded elements, except for heads, showing the advantages of relief in terms of durability. High relief has remained the ascendant form for reliefs with figures in Western sculpture, also existence common in Indian temple sculpture. Smaller Greek sculptures such every bit private tombs, and smaller decorative areas such as friezes on big buildings, more than oft used low relief.

Hellenistic and Roman sarcophagus reliefs were cut with a drill rather than chisels, enabling and encouraging compositions extremely crowded with figures, similar the Ludovisi Battle sarcophagus (250–260 CE). These are as well seen in the enormous strips of reliefs that wound effectually Roman triumphal columns. The sarcophagi in particular exerted a huge influence on after Western sculpture. The European Middle Ages tended to apply high relief for all purposes in stone, though similar Aboriginal Roman sculpture, their reliefs were typically non every bit high as in Ancient Hellenic republic.[viii] Very high relief re-emerged in the Renaissance, and was peculiarly used in wall-mounted funerary art and later on Neoclassical pediments and public monuments.

In the Buddhist and Hindu art of India and Southeast Asia, high relief can also be plant, although it is non equally mutual every bit low to mid-reliefs. Famous examples of Indian high reliefs can be found at the Khajuraho temples, with voluptuous, twisting figures that often illustrate the erotic Kamasutra positions. In the ninth-century Prambanan temple, Fundamental Java, high reliefs of Lokapala devatas, the guardians of deities of the directions, are found.

The largest high relief sculpture in the world is the Rock Mountain Confederate Memorial in the U.Due south. land of Georgia, which was cut 42 feet deep into the mountain,[9] and measures 90 feet in pinnacle, 190 anxiety in width,[10] and lies 400 feet above the ground.[11]

Sunk relief [edit]

A sunk-relief depiction of Pharaoh Akhenaten with his wife Nefertiti and daughters. The primary background has non been removed, just that in the immediate vicinity of the sculpted grade. Note how strong shadows are needed to define the epitome.

Sunk or sunken relief is largely restricted to the art of Ancient Egypt where it is very common, becoming afterward the Amarna menstruation of Ahkenaten the dominant type used, equally opposed to low relief. It had been used before, merely mainly for big reliefs on external walls, and for hieroglyphs and cartouches. The image is fabricated past cut the relief sculpture itself into a flat surface. In a simpler form the images are commonly generally linear in nature, like hieroglyphs, only in most cases the effigy itself is in depression relief, but set within a sunken area shaped circular the image, so that the relief never rises beyond the original flat surface. In some cases the figures and other elements are in a very depression relief that does non rise to the original surface, simply others are modeled more fully, with some areas rising to the original surface. This method minimizes the work removing the background, while assuasive normal relief modelling.

The technique is well-nigh successful with strong sunlight to emphasise the outlines and forms past shadow, as no try was made to soften the edge of the sunk surface area, leaving a confront at a correct-angle to the surface all around information technology. Some reliefs, especially funerary monuments with heads or busts from aboriginal Rome and later Western fine art, leave a "frame" at the original level around the edge of the relief, or place a head in a hemispherical recess in the cake (see Roman example in gallery). Though essentially very similar to Egyptian sunk relief, simply with a background space at the lower level effectually the effigy, the term would not normally be used of such works.

Information technology is also used for carving messages (typically om mani padme hum) in the mani stones of Tibetan Buddhism.

Counter-relief [edit]

Sunk relief technique is not to exist confused with "counter-relief" or intaglio every bit seen on engraved jewel seals—where an prototype is fully modeled in a "negative" way. The image goes into the surface, and so that when impressed on wax it gives an impression in normal relief. However many engraved gems were carved in cameo or normal relief.

A few very late Hellenistic monumental carvings in Arab republic of egypt use total "negative" modelling equally though on a gem seal, perhaps as sculptors trained in the Greek tradition attempted to use traditional Egyptian conventions.[12]

Modest objects [edit]

Small-scale reliefs take been carved in diverse materials, notably ivory, forest, and wax. Reliefs are oft found in decorative arts such every bit ceramics and metalwork; these are less often described every bit "reliefs" than equally "in relief". Small statuary reliefs are often in the form of "plaques" or plaquettes, which may be set in furniture or framed, or just kept as they are, a popular form for European collectors, especially in the Renaissance.

Various modelling techniques are used, such repoussé ("pushed-back") in metalwork, where a sparse metal plate is shaped from backside using diverse metallic or wood punches, producing a relief image. Casting has as well been widely used in bronze and other metals. Casting and repoussé are oftentimes used in concert in to speed upward production and add greater detail to the final relief. In stone, as well as engraved gems, larger hardstone carvings in semi-precious stones have been highly prestigious since aboriginal times in many Eurasian cultures. Reliefs in wax were produced at to the lowest degree from the Renaissance.

Carved ivory reliefs have been used since aboriginal times, and because the material, though expensive, cannot normally be reused, they have a relatively high survival rate, and for example consular diptychs represent a large proportion of the survivals of portable secular art from Tardily Antiquity. In the Gothic period the carving of ivory reliefs became a considerable luxury manufacture in Paris and other centres. Besides as small-scale diptychs and triptychs with densely packed religious scenes, usually from the New Testament, secular objects, usually in a lower relief, were too produced.

These were oft round mirror-cases, combs, handles, and other small-scale items, but included a few larger caskets like the Casket with Scenes of Romances (Walters 71264) in Baltimore, Maryland, in the Us. Originally they were very frequently painted in bright colours. Reliefs can exist impressed by stamps onto clay, or the clay pressed into a mould bearing the design, every bit was usual with the mass-produced terra sigillata of Aboriginal Roman pottery. Decorative reliefs in plaster or stucco may be much larger; this course of architectural decoration is institute in many styles of interiors in the mail-Renaissance Due west, and in Islamic architecture.

Gallery [edit]

-

Sunk relief as low relief within a sunk outline, from the Luxor Temple in Egypt, carved in very difficult granite

-

depression relief inside a sunk outline, linear sunk relief in the hieroglyphs, and high relief (right), from Luxor

-

Low to mid-relief, 9th century, Borobudur. The temple has 1,460 panels of reliefs narrating Buddhist scriptures.

-

Roman funerary relief with frame at original level, merely not sunk relief

-

-

-

Side view of mid-relief: Madonna and Kid, marble of c. 1500/1510 by an unknown north Italian sculptor

-

Robert Gould Shaw Memorial, 1897, Boston, combining costless-standing elements with high and low relief

-

A relatively mod loftier relief (depicting shipbuilding) in Bishopsgate, London. Note that some elements jut out of the frame of the image.

-

Reliefs past mod artists [edit]

Modern artists such as Paul Gauguin, Ernst Barlach, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Pablo Picasso, Henry Moore up to Ewald Matare have created reliefs, in contemporary art, for example, Ingo Kühl should be mentioned.

-

Ernst Barlach, Affections of Hope, 1933, Saint Mary parish church in Güstrow

-

Henry Moore, Relief No. 1, 1959, Bronze, at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem

-

Ewald Matare, master portal with bronze door, 1958–1960, church St. Lambertus, Düsseldorf

Notable reliefs [edit]

Notable examples of awe-inspiring reliefs include:

- Aboriginal Egypt: Most Egyptian temples, e.g. the Temple of Karnak

- Assyria: A famous collection is in the British Museum, Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser 3

- Ancient Persia: Persepolis, and rock-face reliefs at Naqsh-e Rustam and Naqsh-east Rajab

- Ancient Greece: The Parthenon Marbles, Bassae Frieze, Groovy Altar of Pergamon, Ludovisi Throne

- Mesopotamia: Ishtar Gate of Babylon

- Aboriginal Rome: Ara Pacis, Trajan'due south Column, Column of Marcus Aurelius, triumphal arches, Portonaccio sarcophagus

- Medieval Europe: Many cathedrals and other churches, such as Chartres Cathedral and Bourges Cathedral

- Bharat: Sanchi, base of the Lion Capital of Asoka, the stone-cutting Elephanta Caves and Ellora Caves, Khajuraho temples, Mahabalipuram with the Descent of the Ganges, and many Due south Indian temples, Unakoti grouping of sculptures (bas-relief) at Kailashahar, Unakoti District, Tripura, India

- South-East asia: Borobodur in Java, Angkor Wat in Cambodia,

- Glyphs, Mayan stelae and other reliefs of the Maya and Aztec civilizations

- United States: Stone Mountain, Robert Gould Shaw Memorial, Boston, Mount Rushmore National Memorial

- UK: Base panels of Nelson'south Column, Frieze of Parnassus

Smaller-scale reliefs:

- Ivory: Nimrud ivories from much of the Almost Due east, Tardily Antiquarian Consular diptychs, the Byzantine Harbaville Triptych and Veroli Casket, the Anglo-Saxon Franks Casket, Cloisters Cantankerous.

- Argent: Warren Cup, Gundestrup cauldron, Mildenhall Treasure, Berthouville Treasure, Missorium of Theodosius I, Lomellini Ewer and Basin.

- Gold: Berlin Gold Hat, Bimaran catafalque, Panagyurishte Treasure

- Glass: Portland Vase, Lycurgus Cup

See also [edit]

- Rock relief

- Multidimensional fine art

- Pargetting – English exterior plaster reliefs

- Relief press – a different concept

- Repoussé and chasing – a metalworking technique

Notes [edit]

- ^ "Relief". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2012-05-31. Retrieved 2012-05-31 .

- ^ In modern English language, but "high relief"; alto-rilievo was used in the 18th century and a little beyond, while haut-relief has surprisingly found a niche, restricted to archaeological writing, in recent decades afterwards information technology was used in under-translated French texts most prehistoric cave fine art, and copied even past English writers. Its apply is to be deprecated.

- ^ Murray, Peter & Linda, Penguin Dictionary of Art & Artists, London, 1989. p. 348, Relief; bas-relief remained mutual in English language until the mid 20th century.

- ^ For example Avery in Grove Art Online, whose long article on "Relief sculpture" barely mentions or defines them, except for sunk relief.

- ^ Murray, 1989, op.cit.

- ^ Avery, half-dozen

- ^ Avery, vii

- ^ Avery, ii and three

- ^ Boissoneault, Lorraine (August 22, 2017). "What Will Happen to Stone Mountain, America's Largest Amalgamated Memorial?". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "50 things you might non know about Stone Mountain Park". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. July 10, 2018. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ McKay, Rich (July three, 2020). "The world's largest Confederate Monument faces renewed calls for removal". Reuters. Archived from the original on July three, 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ Barasch, Moshe, Visual Syncretism: A Case Study, pp. 39–43 in Budick, Stanford & Iser, Wolfgang, eds., The Translatability of cultures: figurations of the infinite between, Stanford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8047-2561-6 (ISBN 978-0-8047-2561-three).

- ^ Kleiner, Fred South.; Mamiya, Christin J. (2006). Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective – Volume 1 (12th ed.). Belmont, California, The states: Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 20–21. ISBN0-495-00479-0.

References [edit]

- Avery, Charles, in "Relief sculpture". Grove Art Online. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

External links [edit]

- Heilbrunn Timeline of Fine art History, "American Relief Sculpture", Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Reliefs. |

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relief

0 Response to "How Is Relief in Art Different Than a 3d Sculptre"

Postar um comentário